So much is known about Dupuytren; much more needs to be known.

Dupuytren probably isn’t one single diagnosis or one single disease. It’s the end result of overlapping causes. It’s a late effect of many possible causes, the same way similar looking scars can be the late effects of different injuries – cuts, burns, blunt trauma and others. The same way that diabetes can be the end result of childhood viral infection, adult obesity, pregnancy, certain drugs, and other causes. There are different types of scars, different types of diabetes, and different types of Dupuytren. Dupuytren isn’t just variable or unpredictable. It’s multiple diseases which look the same in their final stages.

What does “severe” Dupuytren mean compared to “mild” Dupuytren? It depends who you ask. To the surgeon, severe may mean fingers that are more severely bent, or a technically difficult operation for the surgeon, or a high risk of recurrence after a corrective procedure. To the patient, severe may mean how much it interferes with normal activities, or how it looks, how fast it changes, or how much it hurts – independent of how bent the fingers are. To the biologist, severe may mean what the tissue looks like under the microscope, or how cells behave in a laboratory, or results of blood tests.

What is “Dupuytren diathesis”? Recurrence after treatment is an unsolved problem. Diathesis came from an effort to have some way to predict how likely people are to have a recurrence. Without a blood test, surgeons only had a person’s story to go on. The original list was four diathesis factors:

• a family history of DD

• both hands with DD

• knuckle pads (also called Garrod pads or dorsal Dupuytren nodules)

• Ledderhose disease (plantar fibromatosis).

These diathesis factors have since been reformulated by different authors to include

• age of onset younger than 50

• parent or sibling with disease (rather than any family history)

• Peyronie disease (fibrous nodules and contracture of the penis)

• more than two digits involved

• male gender

• Caucasian ancestry

• thumb or index involvement

The overall risk of recurrence after surgery goes up with more diathesis factors.

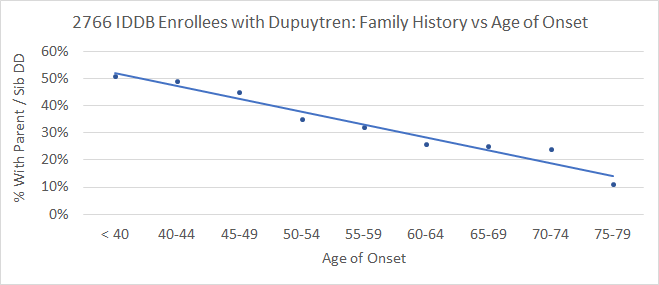

How scientific is this? Not very, if “scientific” means that different researchers have tested the same thing and have come to the same conclusions. There’s open disagreement about whether some of these diathesis factors are valid and about how much influence each factor has. The data seems strongest for early age of onset and for close family history. This is a graph of IDDB enrollees with Dupuytren, showing how having a parent or sibling with Dupuytren correlates with age of onset:

The younger one is when Dupuytren first appears, the more likely one is to have a close relative with Dupuytren – and vice versa.

How common is diathesis? It’s a minority of Dupuytren patients. Published reports are 3-5% of people having treatment for Dupuytren contracture have diathesis. I reviewed my patient records using these three factors to define diathesis:

• age of onset younger than 50

• parent and/or sibling with DD

• knuckle pads, Ledderhose or both

4% of my Dupuytren contracture patients had all three criteria. 10% of IDDB enrollees have all three of these criteria.

If I have diathesis, do I have the bad Dupuytren gene? No, because all large genetic studies on Dupuytren in the last 10 years point to many genes on different chromosomes. Dupuytren likely involves many combinations of different genes, which makes genetic research very challenging. This is why the focus of the IDDB goes beyond genes, to the common biology producing the disease.

If I don’t have diathesis, am I off the hook? No. in addition to inherited risk, there are age-related changes called epigenetic effects, part of the big picture of why we age. Aging isn’t just our bodies wearing out; it’s our bodies changing from the cumulation of age-related epigenetic effects on the immune, inflammation, and tissue repair systems. Other factors, such as diabetes, high cholesterol, smoking, chronic heavy drinking also stress these systems. These are the same systems at play in Dupuytren disease, which explains why the risk of Dupuytren goes up steadily with age.

If I have diathesis factors, am I doomed? No. Diathesis means only one thing: a greater risk of recurrence after treatment. It affects probabilities, but it’s not black and white. Some people with a close family history of Dupuytren, early onset, and Ledderhose have many treatments and many recurrences over their lifetime – but some don’t.

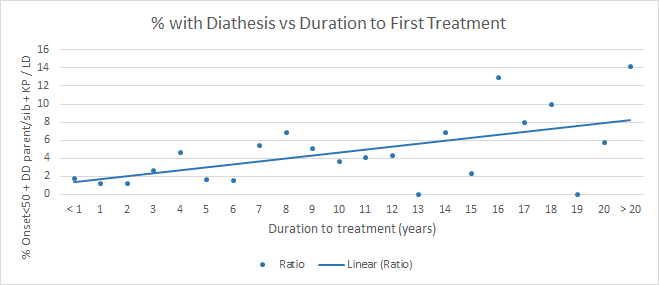

Do people with diathesis develop contractures more quickly than other Dupuytren patients? Not necessarily. One might think that early onset means more rapid progression, but it’s more complicated than that. In a chart review of my patients, looking at the practical issue of how long people had the disease before they came in for their first treatment, I was surprised to see the percent of people with diathesis went up with the longer it took for them to seek treatment. Here, using the same 3 criteria (age of onset, family history, and lumps outside the palm), I found that the less time it took for people to seek treatment for bent fingers the less likely people were to have diathesis. In other words, people with diathesis on average were slower to develop bent fingers than those without.

This is the opposite of what I expected. I found the is seen when comparing duration until first treatment versus how many joints were affected, how many fingers were affected, what the overall bend was adding up all bent joints, and others. In this data, diathesis did not correlate with faster progression of contracture.

How is that possible? One thought is that the longer people have the diagnosis, the more time passes for their close relatives to develop Dupuytren – but that doesn’t go far enough to explain this finding. A possible game-changing explanation might be that rather than diathesis resulting in faster progression, it correlates instead with persistent progression.

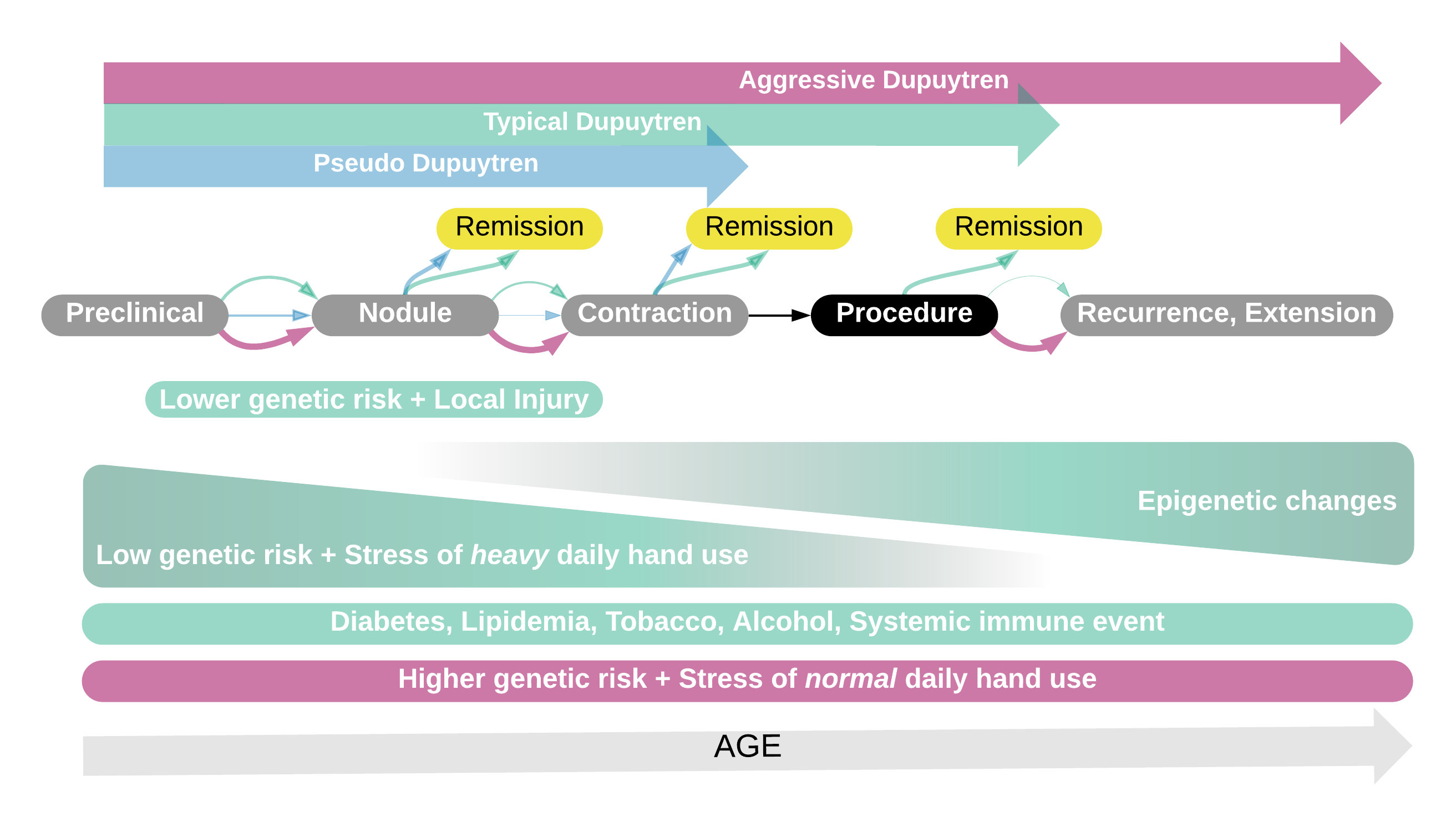

What does this mean? It means that there may be 3 overlapping Dupuytren scenarios: Dupuytren diathesis, pseudo-Dupuytren, and typical Dupuytren. People who develop Dupuytren at a younger age are more likely to have an inherited genetic risk and have it active longer with more changes in their tissues by the time they are treated. Their genes don’t change with surgery, and they are more likely to have it come back after treatment. That’s Dupuytren diathesis. People with less of a genetic predisposition can develop Dupuytren when they are young, but more often following some injury or triggering event. They may not progress to the need for treatment and are genetically less at risk for it to come back after treatment. That’s pseudo-Dupuytren. Finally, people with less genetic risk can accumulate epigenetic changes to a variable degree resulting in more or less progressive Dupuytren disease later in life. That’s typical Dupuytren disease, and that’s the most common scenario for people who have procedures for Dupuytren contracture. This is just a theory, trying to get a handle on what’s been observed about Dupuytren. It doesn’t explain all of the outliers. Some people develop acute Dupuytren with rapid progression of one finger. Some people suddenly develop Dupuytren and knuckle pads in both hands, Peyronie, Ledderhose in both feet, frozen shoulder almost at the same time. Some people have overlap with other connective tissue diseases, or lumps and contractures that are not part of the typical Dupuytren picture. Are these just due to terrible luck or are they completely different diseases? To answer that question, we must first understand the biology of Dupuytren and have some way to measure that biology. We need a Dupuytren blood test. That’s the point of the International Dupuytren Data Bank. If you haven’t enrolled, now is the time: https://DupStudy.com. If you have, recruit others! This is a complicated problem. Working together will give us the best chance of answering these questions and creating a future without Dupuytren disease.

This is just a theory, trying to get a handle on what’s been observed about Dupuytren. It doesn’t explain all of the outliers. Some people develop acute Dupuytren with rapid progression of one finger. Some people suddenly develop Dupuytren and knuckle pads in both hands, Peyronie, Ledderhose in both feet, frozen shoulder almost at the same time. Some people have overlap with other connective tissue diseases, or lumps and contractures that are not part of the typical Dupuytren picture. Are these just due to terrible luck or are they completely different diseases? To answer that question, we must first understand the biology of Dupuytren and have some way to measure that biology. We need a Dupuytren blood test. That’s the point of the International Dupuytren Data Bank. If you haven’t enrolled, now is the time: https://DupStudy.com. If you have, recruit others! This is a complicated problem. Working together will give us the best chance of answering these questions and creating a future without Dupuytren disease.

Charles Eaton MD